Final Dispatch From The GPO

ARMY OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC, Headquarters (Dublin Command), 28th April, 1916.

To Soldiers.

This is the fifth day of the establishment of the Irish Republic, and the flag of our country still floats from the most important buildings in Dublin, and is gallantly protected by the Officers and Irish Soldiers in arms throughout the country. Not a day passes without seeing fresh postings of Irish Soldiers eager to do battle for the old cause. Despite the utmost vigilance of the enemy we have been able to get in information telling us how the manhood of Ireland, inspired by our splendid action, are gathering to offer up their lives if necessary in the same holy cause. We are here hemmed in because the enemy feels that in this building is to be found the heart and inspiration of our great movement.

Let us remind you what you have done. For the first time in 700 years the flag of a free Ireland floats triumphantly in Dublin City. The British Army, whose exploits we are for ever having dinned into our ears, which boasts of having stormed the Dardanelles and the German lines on the Marne, behind their Artillery and Machine Guns are afraid to advance to the attack or storm any positions held by our forces. The slaughter they suffered in the first few days has totally unnerved them and they dare not attempt again an Infantry attack on our position.

Our Commandants around us are holding their own. Commandant Daly’s splendid exploit in capturing Linen Hall Barracks we all know. You must know also that the whole population both Clergy and Laity of this district are united in his praises. Commandant MacDonagh is established in an impregnable position reaching from the walls of Dublin Castle to Redmond’s Hill, and from Bishop Street to Stephen’s Green.

(In Stephen’s Green, Commandant Mallin holds the College of Surgeons, one side of the square, a portion of the other side, and dominates the whole Green and all its entrances and exits.) Commandant De Valera stretches in a position from the Gas Works to Westland Row holding Bolands Bakery, Bolands Mills, Dublin South Eastern Railway Works and dominating Merrion Square. Commandant Kent holds the South Dublin Union and Guinness’s buildings to Marrow Bone Lane and controls Jamieson St. and district. On two occasions the enemy effected a lodgement and were driven out with great loss.

The men of North County Dublin are in the field, have occupied all the Police Barracks in the district, destroyed all the telegraph system on the Great Northern Railway up to Dundalk, and are operating against the trains of the Midland and Great Western. Dundalk has sent 200 men to march upon Dublin and in the other parts of the North our forces are active and growing.

In Galway Captain Mellows fresh after his escape from an Irish Prison is in the field with his men. Wexford and Wicklow are strong and Cork & Kerry are equally acquitting themselves creditably. (We have every confidence that our Allies in Germany and kinsmen in America are straining every nerve to hasten matters on our behalf.)

As you know, I was wounded twice yesterday and am unable to move about, but have got my bed moved into the firing line and with the assistance of your Officers will be just as useful to you as ever. Courage boys, we are winning and in the hour of our victory let us not forget the splendid women who have everywhere stood by us and cheered us on. Never had man or woman a grander cause, never was a cause more grandly served.

Signed,

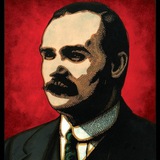

James Connolly,

Commandant General,

Dublin Division.

ARMY OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC, Headquarters (Dublin Command), 28th April, 1916.

To Soldiers.

This is the fifth day of the establishment of the Irish Republic, and the flag of our country still floats from the most important buildings in Dublin, and is gallantly protected by the Officers and Irish Soldiers in arms throughout the country. Not a day passes without seeing fresh postings of Irish Soldiers eager to do battle for the old cause. Despite the utmost vigilance of the enemy we have been able to get in information telling us how the manhood of Ireland, inspired by our splendid action, are gathering to offer up their lives if necessary in the same holy cause. We are here hemmed in because the enemy feels that in this building is to be found the heart and inspiration of our great movement.

Let us remind you what you have done. For the first time in 700 years the flag of a free Ireland floats triumphantly in Dublin City. The British Army, whose exploits we are for ever having dinned into our ears, which boasts of having stormed the Dardanelles and the German lines on the Marne, behind their Artillery and Machine Guns are afraid to advance to the attack or storm any positions held by our forces. The slaughter they suffered in the first few days has totally unnerved them and they dare not attempt again an Infantry attack on our position.

Our Commandants around us are holding their own. Commandant Daly’s splendid exploit in capturing Linen Hall Barracks we all know. You must know also that the whole population both Clergy and Laity of this district are united in his praises. Commandant MacDonagh is established in an impregnable position reaching from the walls of Dublin Castle to Redmond’s Hill, and from Bishop Street to Stephen’s Green.

(In Stephen’s Green, Commandant Mallin holds the College of Surgeons, one side of the square, a portion of the other side, and dominates the whole Green and all its entrances and exits.) Commandant De Valera stretches in a position from the Gas Works to Westland Row holding Bolands Bakery, Bolands Mills, Dublin South Eastern Railway Works and dominating Merrion Square. Commandant Kent holds the South Dublin Union and Guinness’s buildings to Marrow Bone Lane and controls Jamieson St. and district. On two occasions the enemy effected a lodgement and were driven out with great loss.

The men of North County Dublin are in the field, have occupied all the Police Barracks in the district, destroyed all the telegraph system on the Great Northern Railway up to Dundalk, and are operating against the trains of the Midland and Great Western. Dundalk has sent 200 men to march upon Dublin and in the other parts of the North our forces are active and growing.

In Galway Captain Mellows fresh after his escape from an Irish Prison is in the field with his men. Wexford and Wicklow are strong and Cork & Kerry are equally acquitting themselves creditably. (We have every confidence that our Allies in Germany and kinsmen in America are straining every nerve to hasten matters on our behalf.)

As you know, I was wounded twice yesterday and am unable to move about, but have got my bed moved into the firing line and with the assistance of your Officers will be just as useful to you as ever. Courage boys, we are winning and in the hour of our victory let us not forget the splendid women who have everywhere stood by us and cheered us on. Never had man or woman a grander cause, never was a cause more grandly served.

Signed,

James Connolly,

Commandant General,

Dublin Division.

Cartlann

Final Dispatch From The GPO

Originally transcribed by No Other Law ARMY OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC, Headquarters (Dublin Command), 28th April, 1916. To Soldiers. This is the fifth day of [...]

"Connolly's influence upon Pearse was profound and marked. He could have summed Pearse up as one of those real prophets who carve out the future they announce, and he might have felt some pardonable pride that upon national and social fundamentals the accents of the prophet were not at all dissimilar to his own."

- Desmond Ryan, The Man Called Pearse (1919)

- Desmond Ryan, The Man Called Pearse (1919)

...some misguided persons delight in drawing comparisons between the alleged materialism of James Connolly and the incontestable spirituality of Pearse. Moreover, Pearse has defined his social gospel almost as specifically as he has defined his nationalist gospel, it is a gospel startlingly similar to James Connolly's own, a fact of which these very misguided persons are most likely to remain ignorant...

...Men and women, however, devoted to the memories of both men, have fallen into this error of confusing a difference between philosophies of history into a clash of ideals. In reality, no poorer tribute could be paid to Pearse in so far as this comparison betrays a remarkable misunderstanding of his social ideals and outlook....

...It would be easy indeed to prove that however firmly Connolly planted his feet upon the earth, his gaze was ever turned towards the stars. The two great causes of his heart were the ideals he worshipped with a religious fervour. In him love of freedom burned with the intensity of fanaticism, and were lip-service to the things of the spirit all that is needed to constitute a man an idealist many a page from his writings would demonstrate his claim beyond yea or nay. Only a mental snobbery goes in search of such a proof...

... I prefer to consider what Pearse's views were concerning the bread nations no less than men require if they are to live at all. To do so will be to recognize that a great idealist and a true poet considered the physical welfare of a people ranked equally with the firing of their minds or the care of their souls. Nor will it remain longer in doubt whether Pearse's views on social matters shall remain as obscure as were James Fintan Lalor's until Connolly rescued them from newspaper files, libraries, and deliberate neglect.

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

...Men and women, however, devoted to the memories of both men, have fallen into this error of confusing a difference between philosophies of history into a clash of ideals. In reality, no poorer tribute could be paid to Pearse in so far as this comparison betrays a remarkable misunderstanding of his social ideals and outlook....

...It would be easy indeed to prove that however firmly Connolly planted his feet upon the earth, his gaze was ever turned towards the stars. The two great causes of his heart were the ideals he worshipped with a religious fervour. In him love of freedom burned with the intensity of fanaticism, and were lip-service to the things of the spirit all that is needed to constitute a man an idealist many a page from his writings would demonstrate his claim beyond yea or nay. Only a mental snobbery goes in search of such a proof...

... I prefer to consider what Pearse's views were concerning the bread nations no less than men require if they are to live at all. To do so will be to recognize that a great idealist and a true poet considered the physical welfare of a people ranked equally with the firing of their minds or the care of their souls. Nor will it remain longer in doubt whether Pearse's views on social matters shall remain as obscure as were James Fintan Lalor's until Connolly rescued them from newspaper files, libraries, and deliberate neglect.

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

Connolly's influence upon Pearse was profound and marked. He could have summed Pearse up as one of those real prophets who carve out the future they announce, and he might have felt some pardonable pride that upon national and social fundamentals the accents of the prophet were not at all dissimilar to his own. Pearse himself esteemed Connolly as one or the greatest and most forceful men that he had known, while those of us who knew both men are aware of the great affection which existed between them. Emphatically there was no essential clash between their respective ideals although each had travelled by different paths to discover that the sole authentic nationalism is one which seeks to enthrone the Sovereign People. A sentence in the Republican Proclamation reveals a common faith :

" We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies to be sovereign and indefeasible."

Partisans may choose to stress either part of that declaration but in a hundred other equally unmistakable and unequivocal utterances Pearse and Connolly will rise to confute them.

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

" We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies to be sovereign and indefeasible."

Partisans may choose to stress either part of that declaration but in a hundred other equally unmistakable and unequivocal utterances Pearse and Connolly will rise to confute them.

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

James Connolly's views upon the social question are too well known to fall into obscurity. Pearse's social creed is equally clear and unambigious, but circumstances may very well tend to obscure its similarity in essentials with Connolly's teachings.

... The works of Lalor together with close observation of conditions of life in Connacht and Dublin assisted this development considerably. Undoubtedly the Dublin Strike of 1913, whatever glimpses he caught (by no means few) of the great Labour upheavals which shook these countries from 1911 onward, and Connolly's personal influence urged him more and more insistently to consider the issue.

... Misgivings troubled him, no doubt. Internationalism was to him a word of omen as ill as it is still to many Sinn Feiners and Republicans, not to mention the A.O.H. Pacificism which seems to many inseparable from a Labour movement never appealed to him, and to the last he found no use for Tolstoy or other apostles of peace, not even appreciating their chief as an artist. Connolly's militancy was more to his liking. " Even the Socialists," Pearse writes somewhere, " who want universal peace, propose to reach it by universal war ; and so far they are sensible! " The pre-war solidarity of the workers seemed to him to threaten to obliterate the lines of national demarcation, and in such an obliteration he feared another imperialist triumph. While Connolly cried scornfully that his quarrel was with the British Government in Ireland...

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

... The works of Lalor together with close observation of conditions of life in Connacht and Dublin assisted this development considerably. Undoubtedly the Dublin Strike of 1913, whatever glimpses he caught (by no means few) of the great Labour upheavals which shook these countries from 1911 onward, and Connolly's personal influence urged him more and more insistently to consider the issue.

... Misgivings troubled him, no doubt. Internationalism was to him a word of omen as ill as it is still to many Sinn Feiners and Republicans, not to mention the A.O.H. Pacificism which seems to many inseparable from a Labour movement never appealed to him, and to the last he found no use for Tolstoy or other apostles of peace, not even appreciating their chief as an artist. Connolly's militancy was more to his liking. " Even the Socialists," Pearse writes somewhere, " who want universal peace, propose to reach it by universal war ; and so far they are sensible! " The pre-war solidarity of the workers seemed to him to threaten to obliterate the lines of national demarcation, and in such an obliteration he feared another imperialist triumph. While Connolly cried scornfully that his quarrel was with the British Government in Ireland...

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

Forwarded from Archiving Irish Diversity Stuff (AIDS)

Person I know started a project of narrating Irish nationalist texts to create audio books for people too busy to sit down and read.

They've already uploaded the first two articles of the Murder Machine and hopefully will have more coming out over the next few days

Give them a follow if you're interested:

Youtube Channel Here

Check out Telegram Channel Here

They've already uploaded the first two articles of the Murder Machine and hopefully will have more coming out over the next few days

Give them a follow if you're interested:

Youtube Channel Here

Check out Telegram Channel Here

YouTube

1 The Broad Arrow

We begin the narration of The Coming Revolution with the series of articles penned by Padraig Pearse known as "The Murder Machine."

We begin with the first article "The Broad Arrow."

#pearse #nationalism #1916 #comingrevolution #ireland #irish

We begin with the first article "The Broad Arrow."

#pearse #nationalism #1916 #comingrevolution #ireland #irish

"Pearse and Connolly, much as they may have differed upon questions of philosophy, were not given to cant about the one's spirituality and the other's materialism. As their writings bear witness, they knew how amusingly superficial such a comparison is. Connolly worshipped at different shrines of the goddess freedom in two continents, and spent his life at last as he would have wished in Ireland. Pearse served freedom in Ireland alone, but had fate brought him elsewhere, I dare believe his story would have been much the same. The ideal of both had different manifestations, but in the end it was one and the same."

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

Forwarded from Cartlann.org

We just launched 8 new additions to our James Connolly collection. A personal thanks to @MacGhW for his help in transcribing them. Go take a peak!

https://cartlann.org/authors/james-connolly/

https://cartlann.org/authors/james-connolly/

Cartlann

James Connolly

James Connolly (1868-1916) was the foremost Irish socialist republican of his time. He was the leader of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), founder and leader [...]

Forwarded from Díghalldaigh Éire

Ceol Éireannach

The best music by Irish artists

Use keyword search when posts get too many

https://t.me/ceoleireannach

The best music by Irish artists

Use keyword search when posts get too many

https://t.me/ceoleireannach

Connolly was, indeed, the most terrific expression in a personality of the modern revolutionary spirit that these islands have known. Pearse undoubtedly was the grandest incarnation in men of Irish blood of the ancient tradition of Irish nationhood, but these two men, unlike many of the disciples of either, knew better than to stick fast in a morass of phrases.

Connolly's influence on Pearse as before mentioned was considerable. The meeting of these two men of characters so diverse in many ways during the early months of 1914 was, indeed, historic. Until then neither had known the other intimately. Years before a speech delivered by Connolly before a students' debating society in defence of woman's suffrage had left an indelible impression on Pearse's memory. Since then both had worked in fields far apart, one striving to spread Socialist ideas in Ireland and America, to shake the general apathy as regards social issues, to build up an army of labour, to descend, as Mr. Robert Lynd has well said, into the hell of Irish poverty with a burning heart, the other squandering without regret the glorious years of his youth to re-create an Irish literature, to quicken with his idealist faith the dying national consciousness and bring an ancient chivalry and a new vision into the land. In due course the war in Europe threw them together. It would have required no bold prophet to foresee events must move hence- forward in unwonted ways.

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

Connolly's influence on Pearse as before mentioned was considerable. The meeting of these two men of characters so diverse in many ways during the early months of 1914 was, indeed, historic. Until then neither had known the other intimately. Years before a speech delivered by Connolly before a students' debating society in defence of woman's suffrage had left an indelible impression on Pearse's memory. Since then both had worked in fields far apart, one striving to spread Socialist ideas in Ireland and America, to shake the general apathy as regards social issues, to build up an army of labour, to descend, as Mr. Robert Lynd has well said, into the hell of Irish poverty with a burning heart, the other squandering without regret the glorious years of his youth to re-create an Irish literature, to quicken with his idealist faith the dying national consciousness and bring an ancient chivalry and a new vision into the land. In due course the war in Europe threw them together. It would have required no bold prophet to foresee events must move hence- forward in unwonted ways.

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

He announced his brotherly union with Connolly was a union of thought as well as deeds, and that the national freedom both strove for extended to a people's wealth and lands as well as to their liberties and Governmental systems. Once and for all, beyond a shadow of doubt, he recorded these convictions in written words before the storm broke and he knew now or never was the opportune moment to proclaim his social faith. Thereafter he had "no more to say."

- Desmond Ryan, The Man Called Pearse (1919)

- Desmond Ryan, The Man Called Pearse (1919)

This dissatisfaction with current ideals and institutions drove him to seek a new educational inspiration in a return to the Sagas. An heroic tale was more essentially a factor in education than all the propositions of Euclid ; the story of Joan of Arc more charged with meaning than a thousand algebras. He claimed, too, that had the old Irish. Sagas swayed Europe to the extent the Renaissance has that inspiration would have saved many a righteous and noble cause. By an easy transition Pearse passed from this mood to proclaim the thing that was coming, to salute with Connolly the risen people.

He announced his brotherly union with Connolly was a union of thought as well as deeds, and that the national freedom both strove for extended to a people's wealth and lands as well as to their liberties and Governmental systems. Once and for all, beyond a shadow of doubt, he recorded these convictions in written words before the storm broke and he knew now or never was the opportune moment to proclaim his social faith. Thereafter he had " no more to say."

LABOUR IN IRISH HISTORY, and in a smaller degree THE RE-CONQUEST OF IRELAND, have left their mark upon The Sovereign People. This pamphlet is an explicit statement of P. H. Pearse's social ideals, the concluding one of a series where he re-states the gospel of Nationalism as defined by Tone, Davis, Mitchel and Lalor. Therein he examines the lives and teachings of the two last. In the previous booklets he had insisted upon the spiritual fact of nationality, upon the separatist tradition in history, upon the necessity of physical freedom to preserve the spiritual fact and vindicate the tradition. His argument might have been expressed in Connolly's words :

He announced his brotherly union with Connolly was a union of thought as well as deeds, and that the national freedom both strove for extended to a people's wealth and lands as well as to their liberties and Governmental systems. Once and for all, beyond a shadow of doubt, he recorded these convictions in written words before the storm broke and he knew now or never was the opportune moment to proclaim his social faith. Thereafter he had " no more to say."

LABOUR IN IRISH HISTORY, and in a smaller degree THE RE-CONQUEST OF IRELAND, have left their mark upon The Sovereign People. This pamphlet is an explicit statement of P. H. Pearse's social ideals, the concluding one of a series where he re-states the gospel of Nationalism as defined by Tone, Davis, Mitchel and Lalor. Therein he examines the lives and teachings of the two last. In the previous booklets he had insisted upon the spiritual fact of nationality, upon the separatist tradition in history, upon the necessity of physical freedom to preserve the spiritual fact and vindicate the tradition. His argument might have been expressed in Connolly's words :

"Slavery is a thing of the soul before it embodies itself in the material things of the world. I assert that before a nation can be reduced to slavery its soul must have been cowed, intimidated or corrupted by the oppressor. Only when so cowed, intimidated or corrupted, does the soul of a nation cease to urge forward its body to resist the shackles of slavery ; only when the soul so surrenders does any part of the body consent to make truce with the foe of its national existence. When the soul is conquered the articulate expression of the voice of the nation loses its defiant accent and, taking on the whining colour of com- promise, begins to plead for the body. The unconquered soul asserts itself and declares its sanctity to be more important than the interests of the body ; the conquered soul ever pleads first that the body may be saved even if the soul be damned. For generations this conflict between the sanctity of the soul and the interests of the body has been waged in Ireland. ... In fitful moments of spiritual exaltation Ireland accepted that idea, and such men as O'Donovan Rossa becoming possessed of it, became thence- forth the living embodiment of that gospel."

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

...we shall have travelled far beyond enduring social unrighteousness because men and nations do not live by bread alone. Two men in Dublin knew that once before, when a manly figure in green grasped the other's hand beneath the Post Office porch, crying, "Thank God, Pearse, we have lived to see this day!"

- Desmond Ryan, The Man Called Pearse (1919)

- Desmond Ryan, The Man Called Pearse (1919)

What is Pearse's definition of a nation ? A Sovereign People ! His ideal was no mere political sovereignty, although he demanded this also in the fullest degree, but a sovereignty which extends to the soil and factories of Ireland that the stubborn and unterrified working class, the common people whom he hails with enthusiasm and pride, as the unpurchasable and unfaltering guardians of national liberties may say with truth of their nation that it is the family in large knit together by ties human and kindly. He salutes " the more virile labour organiza- tions of to-day " as heirs to Lalor's teaching, nor do vague accusations of anarchism or materialism prevent him from announcing himself as one who is heart to heart with them. In effect, he agrees with Lalor, who held separation valueless unless it placed, not certain rich men merely, but the actual people of Ireland in effectual possession of the soil and resources of their country.

Here may conclude this short sketch of the social ideals of P. H. Pearse, but this mere formal outline is of little use to those who do not recognize the democratic instinct behind every line Pearse wrote. Connolly recognized it and confessed to his friends that he had always been attracted towards Pearse, in whom he felt some quality above the average of Nationalist politicians.

[...]

It is not claimed here that Pearse saw eye to eye with James Connolly upon the question of Socialism, inasmuch as Pearse did not adhere to, nor had he indeed studied, the Socialist system that James Connolly spent a life-time in preaching...

...It is not even sought to establish whether Pearse was a Socialist or not. If Socialism be, as we hear often, the common ownership of the means of wealth-production, distribution and exchange by and in the interest of the whole community, then it should be difficult to refuse the designation to the man who wrote The Sovereign People.

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

Here may conclude this short sketch of the social ideals of P. H. Pearse, but this mere formal outline is of little use to those who do not recognize the democratic instinct behind every line Pearse wrote. Connolly recognized it and confessed to his friends that he had always been attracted towards Pearse, in whom he felt some quality above the average of Nationalist politicians.

[...]

It is not claimed here that Pearse saw eye to eye with James Connolly upon the question of Socialism, inasmuch as Pearse did not adhere to, nor had he indeed studied, the Socialist system that James Connolly spent a life-time in preaching...

...It is not even sought to establish whether Pearse was a Socialist or not. If Socialism be, as we hear often, the common ownership of the means of wealth-production, distribution and exchange by and in the interest of the whole community, then it should be difficult to refuse the designation to the man who wrote The Sovereign People.

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

Pearse himself refuses the designation in several places throughout his writings. He dreaded certain aspects of modern Socialist teachings, and would no doubt have damned them with the rest of modern evil. Many Socialists will be no doubt equally prompt to find evasions and unorthodoxies in his statement of his social creed. They will prefer to misunder- stand the idealistic and nationalist inspiration which swayed him. They will, unlike Connolly, continue to emphasise the phrases in the Republican Proclamation anent the right of the Irish people to the ownership of Ireland, and deem Irish destines un- fettered and uncontrolled a mere rhetorical phrase until another Pearse rises to confuse them. Perhaps the war will avert the need for another Pearse to confute them. Certainly they would never convert the idiots who babble about Connolly's materialism and Pearse's idealism without tremendous emphasis indeed. In Pearse they will find that breath of freedom's eternal spirit which has moulded all their systems and creeds.

In any case, let us have no more foolish comparisons or sickly idealisms which have been greater cloaks for evil than all the materialisms in history. Let us, in short, remember what Pearse's social ideals were, or we shall misunderstand his greatness. For even when we have returned to the Sagas and burned our rent-books as Pearse advised us, it is, at least, problematical whether we shall all dismiss Karl Marx as quite so finished an instrument of the devil as Pearse dismissed Adam Smith. But, assuredly we shall have travelled far beyond enduring social unrighteousness because men and nations do not live by bread alone. Two men in Dublin knew that once before, when a manly figure in green grasped the other's hand beneath the Post Office porch, crying, "Thank God, Pearse, we have lived to see this day!"

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)

In any case, let us have no more foolish comparisons or sickly idealisms which have been greater cloaks for evil than all the materialisms in history. Let us, in short, remember what Pearse's social ideals were, or we shall misunderstand his greatness. For even when we have returned to the Sagas and burned our rent-books as Pearse advised us, it is, at least, problematical whether we shall all dismiss Karl Marx as quite so finished an instrument of the devil as Pearse dismissed Adam Smith. But, assuredly we shall have travelled far beyond enduring social unrighteousness because men and nations do not live by bread alone. Two men in Dublin knew that once before, when a manly figure in green grasped the other's hand beneath the Post Office porch, crying, "Thank God, Pearse, we have lived to see this day!"

(The Man Called Pearse, D. Ryan, Chapter VII)